How the Index of American Design Kickstarted Edward Loper’s Art Career

The acclaimed Delaware artist first brought his artistic ambitions to life drawing decorative art objects for the Work Progress Administration project.

Would Edward Loper have formally pursued art had it not been for the Index of American Design project? “I would not have even thought about it. No, I would not have become an artist, no.”

Today, Loper is known for his stylistic approach and use of color. The acclaimed Delaware artist first brought his artistic ambitions to life drawing decorative art objects for the Index.

An Artist Gets His Start

Loper was fascinated by art and color from childhood. He taught himself to draw while attending segregated schools on the east side of Wilmington, Delaware.

In his youth, Loper primarily focused on drawing and using “showcard” colors—ones best suited for smaller cards and graphic art. He recalled “painting on my own without any knowledge of what the painting was about at all. The fact is, I didn’t know one artist. I had never heard of any of them.”

As a young African American man, Loper faced a series of challenges, including a segregated society and art scene. He came of age during the Great Depression, and struggled to find work to provide for his family.

As Loper recounted in a 1985 interview,

This changed in 1936, when his then wife Viola Cooper learned of a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project that was looking for artists. After informing staff that he could draw and paint, Loper was hired. He joined three other artists who were already working on the Index of American Design project in Delaware.

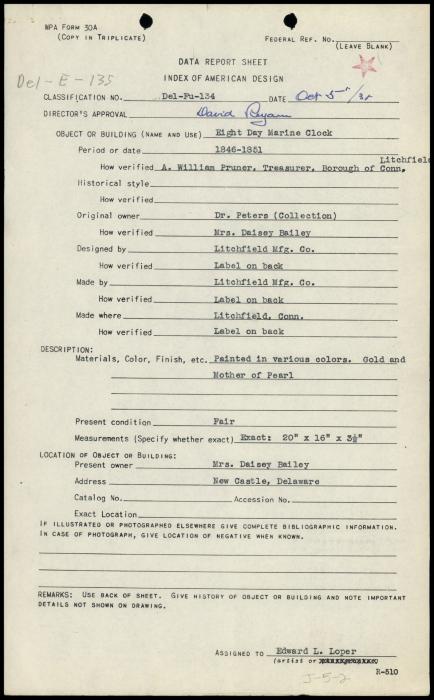

Each object in the Index had a data report sheet that provided a wealth of information, including about its owner and place of origin. That’s how we know that this marine clock Loper documented was originally made it Litchfield, Connecticut, in the mid-1800s—and that it was owned by Mrs. Daisey Bailey of New Castle, Delaware.

Drawing for the Index of American Design

Unlike other Federal Arts Projects, the Index focused on documentation rather than expression. Its aim was to produce a pictorial survey of American crafts and decorative arts. In fact, every object was accompanied by a data report sheet that included in-depth information: its owner, location, description, and assigned artist.

The process started with a supervisor identifying objects of interest in private collections and historical societies. As Loper recalled, most people would not allow the project team to create drawings in their homes. Historical societies or museums were more open to artists working onsite.

To assist the artists in their renderings, each object was photographed from several different angles. In the studio, these photographs hung on strings to help convey a sense of perspective, lighting, and depth.

Artists would then create a series of sketches and watercolor renderings. Loper described the process:

To produce such accurate renderings, many Index artists had to undergo training. This included weekly trips to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where they were encouraged to study artists and techniques. Loper took this a step farther: he also attended local art events in Wilmington. (That is where he was exposed to artist N. C. Wyeth, one of whose paintings he said “was the most important thing I’d ever seen in my life.”)

Compare Loper's preparatory drawing of this corn-themed cream pitcher with his final watercolor. Note how he rendered the texture of the surface of the American Majolica pitcher. The data sheet for the object dates the pitcher to approximately 1820.

After looking closely at the works of various artists, Loper would go home and paint for at least two hours. “I never missed a day of painting for 25 years,” he later said. He focused primarily on depicting local houses, night scenes, and snowy and rainy days. After a Shower, one of the paintings he made during this time, was a night scene from his kitchen window. Loper entered it in the Annual Delaware Show at the Wilmington Society of Fine Arts (now the Delaware Art Museum). He became the first African American artist to win a prize in the show.

And in 1937, the same museum accepted one of his works into its collection. It was one of the very institutions Loper visited as part of his training for the Index.

Loper as an Artist and Teacher

In 1939, Loper was “painting so well,” he said, that “they decided I wasn’t as needed on the Index.” He was transferred to the easel division of the WPA, which allowed him to create paintings of his own design and composition. As a part of this assignment, which lasted until 1941, he also taught art at the Ferris School in Wilmington.

Throughout the 1940s, Loper focused on painting vivid landscapes and cityscapes of Wilmington, which he described as “mood paintings.” By the 1950s, he had transitioned to cubist paintings inspired by Pablo Picasso. In 1963, he went on to attend classes at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, where he studied classical techniques until 1968.

After the WPA, Loper worked at the Allied Kid leather factory, which allowed him to paint on his own time, teach his coworkers, and publicize his work. He went on to teach at the Delaware Art Museum, Delaware College of Art and Design, Lincoln University, and the Jewish Community Center in Wilmington. Loper also taught private classes at his studio.

Edward L. Loper with one of his works exhibited in the 2002 exhibition, Drawing on America's Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives.

Giving Young Artists a Better Chance

Loper was not the only prominent artist to work with the WPA. Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock also worked on the easel division, and Willem de Kooning created murals. “Everybody who was on there got credit for being pretty good at what they were,” Loper said.

Projects like the WPA, Loper emphasized, were critical not only for providing employment but also for encouraging young artists with little access to formal training or education. “I think that would be a very good thing—to have it now,” Loper said, “For young artists who would like to become better at what they do. And some of the things that we need to have more recorded, that would be their job so they could make a living. And then they could do their own painting for the rest of the day, the same way that I did. And it would be a good chance for them. It would give young artists a better chance.”

You may also like

Interactive Article: The Marvelous Details of Joris Hoefnagel’s Animal and Insect Studies

Scroll to discover tiny brushstrokes, hidden meanings, and the immense impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Article: Seven Highlights from the Index of American Design

Peer into the American past with a collection of Great Depression–era watercolors.